Son’s Death Launches Father’s Re-Education into the Dangers of Teen Driving

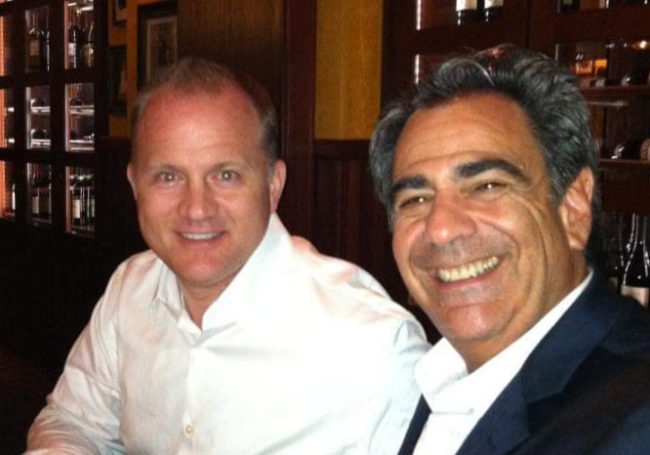

After his son Reid died in a car crash, Tim Hollister helped transform Connecticut’s teen driving laws. The provisions include earlier curfews, no electronic devices, a two-hour teen driving safety course for both teens and their parents and restrictions on who can ride with young drivers. Evermore is dedicating this Father’s Day week to…