Evermore is dedicating this Father’s Day week to bereaved dads who will always be fathers.

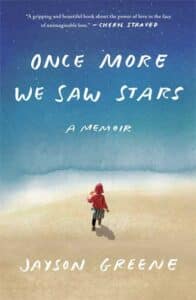

In a new memoir, Once More We Saw Stars, father Jayson Greene vividly recounts the raw feelings after his two-year-old daughter Greta died and his continuous journey through grief.

A stunning accident claimed the life of two-year-old Greta Greene in 2015, when a piece of masonry fell from a building on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and struck her in the head.

In a new memoir, Once More We Saw Stars, her father Jayson Greene vividly recounts the raw feelings after the loss, his journey through grief with his wife Stacy, and the couple’s striving toward hope.

Q. You’ve spoken about writing as a tool for survival. Is that what brought you to write this memoir?

A. Journaling is a common approach to grief. I wrote a book because I’m a writer, but writing is an instinctual thing. I mean, I’ve been to Compassionate Friends meetings and other sorts of grief retreats.

People have written pages and pages and pages about their child or their loss, because writing is a profound way to process grief.

Q. How is promoting the book and talking to people and continually retelling the story?

A. It’s cathartic.

Telling the story of what happened to Greta is a way of testifying. I think that’s probably true for many.

One of the things that you do when you go to a grief support group is — because there might be somebody new there every time — you retell the story. And you know, every time you do that, it’s a way of acknowledging that you’ve been marked, because people might sort of intellectually know, ‘oh, yeah, there’s, there’s Jayson, that horrible thing happened — they lost their daughter, and how tragic.”

But in the course of a regular day, it’s not exactly at the surface of your interactions with people. It’s often several layers down. Sometimes you yourself forget the degree to which you are always grieving that person. I’m doing what most grieving parents do in a somewhat different set of circumstances. And through the sort of conduit of a book, and I’ve written the book, and it’s out there, and people are asking to speak to me.

I am grateful for the fact that I’m able to talk about my Greta all the time right now. And there’s a context for it. And there’s a receptive audience for stories about Greta.

There are a lot of people who will listen to me talk about her life, how much we loved her, how much we still love her. And what happened. So in some ways promoting this book has been healing.

Q. What would you like people to know about Greta?

A. She was very talkative from a very early age. She learned how to talk really early on, around 13 or 14 months- words and some sentences -which was startlingly early. But it gave us a chance to hear a lot of what she thought which was very, very meaningful. We feel very lucky to have had that.

She was very opinionated. And she had a really developed sense of humor. She always seemed to be smiling at a private joke.

Q. What does it mean to be a writer finding the right words and language to convey the vast and continuing consequences of grief?

A. As I’ve talked to people, I have learned a lot about the words that we assigned to our feelings. I’m a writer. And that’s basically what I spent my life doing is assigning words to my feelings, I’ve thought about it maybe a little bit more intensely, because it’s been my focus forever.

Healing has been a word that’s meant something to me. I remember thinking about my grief as a massive wound, even right in the days after the accident, My mind seized on this metaphor of wound care — the idea that I had massive life-threatening wound on my body, and if I didn’t spend every single day cleaning it and tending to it, and changing the bandages and applying salve that it would infect and kill me.

That’s what blunt force trauma, emotionally speaking, feels like. That’s what acute shock and catastrophic loss feels like. It is very literally threatening the fabric of your existence.

Everything you’ve ever understood is completely destroyed in an instant and that does feel life threatening. I mean, it is not going to literally stop your heart. But it feels like annihilation, because it erases everything that you thought you knew, it erases all your context.

Q. Jayson has written a Washington Post column about being a grieving parent on Father’s Day and other holidays. He says people struggle to know what to say to grieving parents.

A. People worry so much about what to say to grieving parents.

I always try to say that you’ll never say the right thing because there is no right thing to say what’s most important is that you listen to the person, and that you’re there for them.

The other thing I would say to that person who’s worried about what to say, is that you might step on a landmine. And that’s also not the worst thing that happened to that person that day.

If you’re talking to someone who’s just lost their kid, you saying something dumb is not going to matter. all that much, because they are grieving something so much larger than you, or your concerns about what to say. The only thing you can really, truly offer — the only true currency you have — is yourself. And if they get mad at you, just take it as part of what you can be there for, but they’re processing a lot of feelings. If they momentarily flare up, and you have the strength to absorb that and sit there with it and allow them to work through it, the chances are that they’ll probably vent at you and then soften and say that they’re sorry. And then you can both sit in that together.

Q. As you have what have other grieving parents connected with?

A. The stuff about the shock really speaks to grieving parents, as much as I can tell.

When I was sort of reeling from the loss, I had the nastiest, most poisonous, bitter thoughts I probably ever had in my life. And they’re all very clearly rendered in the book.

I think a lot of people have felt that — it spoke to memories they had. People have found a lot of resonance in some of those feelings — I don’t know that those kinds of feelings have made it to the page in a lot of published books about grief.

Q. What is your favorite passage in the book?

A. Probably the last two pages where I’m talking both to Harrison (his living son, who is now three years old) and to Greta, because it’s such a hard, hard and long journey to the place where I felt like I could hold them both inside of my heart.

I wrote it shortly after Harrison was born, and he was still very new to the world, closer to where Greta was, than he is now. Now, he’s very much of this world, which is a joyful thing. But you know, it also means that there’s distance between who he is and who Greta was. But in that moment, they were very close. And so I felt like I could sort of address them both. And it was maybe the only time in my life I’ll be able to feel that and so being able to capture that feeling and write it. To have it be the last two pages of the book is very meaningful to me.

Also read:

- Am I Still a Father? — After his son Jon’s death, Ron Kelly helps other fathers live with their grief.

- Two dads, one mission: Better bereavement leave.

- Son’s death launches father’s re-education into the dangers of teen driving.