From Pain to Expression: The Transformative Power of Poetry for Grieving, Systems-Impacted Youth

By Nebeu Shimeles

“She wore her grief, loosely like a battered, faded shawl draped around her shoulders. She had nothing to say.”

– Arundhati Roy, The God of Small Things

Experiencing loss has a transformative effect, forever altering our conception of ourselves, the world around us, and the way we relate to others. As the poet Joshua Turek aptly puts it, “grief makes you into a whole new person and separates you forever from the one you were right before it.” And all of us, in one form or another, will experience bereavement; we have no choice in the matter. But as a society, the response we mount to that loss is well within our control. While each person’s journey through loss is unique, the systemic response to such loss has profound implications for ‘the whole new person’ that emerges in its aftermath.

Meeting Grieving Youth Where They Are

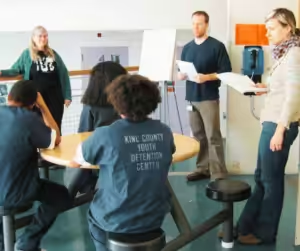

Do we meet people in their moment of need? Do we demonstrate our commitment to their well-being by providing resources and support in helping them make sense of such trauma? At Pongo Poetry Project, these questions are at the forefront of our minds in our work supporting systems-impacted young people.

Do we meet people in their moment of need? Do we demonstrate our commitment to their well-being by providing resources and support in helping them make sense of such trauma? At Pongo Poetry Project, these questions are at the forefront of our minds in our work supporting systems-impacted young people.

When young people are ensnared in the carceral system it is in the wake of a cascading set of systemic failures. Inadequate access to healthcare, substandard educational opportunities, and housing insecurity are systemic factors that contribute to youth incarceration. And the connective tissue between so many of the young people we serve is childhood trauma, and a lack of support in coping with such experiences.

The Lasting Impact of Childhood Trauma

Childhood trauma affects people deeply, often burdening them with confusion, a sense of personal defectiveness, and shame, rendering them unable to express themselves. And we know that youth of color, youth in poverty, and systems-impacted youth experience such trauma at disproportionately higher rates. A 2017 study on racial differences in trauma exposure found that Black youth are 45% more likely to have experienced trauma than white youth. Youth in poverty are 74% more likely to have experienced trauma than those from wealthy families.

Exacerbating this disproportionate burden is the fact that vulnerable youth often lack access to the support services they need to process and cope with such pain. A 2022 report from the African American Knowledge Optimized for Mindfully Healthy Adolescents (AAKOMA) Project found that nearly 30% of youth of color who reported needing mental health treatment did not receive it. It’s within that context, and in response to those factors that young people often harm themselves, others, and their futures as a way of processing their pain.

Unspoken Pain: The Consequences of Suppressed Grief

When people are unable to express and process their traumatic experiences, they may act out their pain through self-destructive and risky behaviors. According to the Centers for Disease Control, adverse childhood experiences are directly correlated with a child developing mental illness, substance misuse issues, and health concerns that negatively impact their ability to learn. Continual exposure to trauma creates “toxic stress,” which can lead to memory problems, difficulty learning, and behavioral challenges. Viewed through this lens, escalating rates of substance use, mental health turmoil, and acts of violence are evidence of the fact that young people are hurting, and lacking the support they need to thrive. Pongo exists to meet this need.

When people are unable to express and process their traumatic experiences, they may act out their pain through self-destructive and risky behaviors. According to the Centers for Disease Control, adverse childhood experiences are directly correlated with a child developing mental illness, substance misuse issues, and health concerns that negatively impact their ability to learn. Continual exposure to trauma creates “toxic stress,” which can lead to memory problems, difficulty learning, and behavioral challenges. Viewed through this lens, escalating rates of substance use, mental health turmoil, and acts of violence are evidence of the fact that young people are hurting, and lacking the support they need to thrive. Pongo exists to meet this need.

Pongo’s Mission: A Safe Space for Self-Expression

On a weekly basis, Pongo provides trauma-informed poetry workshops for young people across Seattle-area juvenile detention centers and residential psychiatric hospitals. While traumatic childhood experiences are all too common, as with all crises, those at the margins are impacted more intensely. According to a 2020 Evermore report on bereavement in the U.S., a staggering 90% of systems-impacted youth have suffered the death of a close loved one, with nearly two-thirds of those young people experiencing the violent loss of a loved one. Lacking an outlet for that pain, it often manifests itself in self-destructive behaviors among young people, with Evermore finding that one-quarter of systems-impacted youth join a gang in the aftermath of their loss.

The young people we serve communicate a desire to be heard and empowered to describe their experiences on their own terms. And in Pongo workshops, our skilled, empathetic, and talented writing mentors offer youth just that. Our impact is facilitated through the connection that our poetry writing mentors cultivate with youth. Mentors who support young people in discovering, developing, and expressing their identities and their perspectives; and by bearing witness to their pain, hopes, stories, and creativity. With generous support from Evermore, Pongo has provided this transformative experience to systems-impacted youth during our 2024-2025 program year.

A Poet’s Journey: From Silence to Self-Expression

One of Pongo’s flagship program sites in the Seattle area is the Echo Glen Children’s Center; a juvenile rehabilitation facility for young people serving criminal sentences. As Arlene, a longtime Pongo mentor puts it, one of the privileges of engaging youth in Pongo poetry writing is being “invited into [their] moments of self-expression and revelation” and observing their “transformation and sense of relief as [they] give voice to their feelings.” Earlier this year, Pongo mentors worked with one youth writer whose poetry and personal story encapsulates the impact of poetry writing and mentorship that Arlene describes.

“When we first sat down, this youth writer was clear with me that he did not consider himself a writer. Then he proceeded to write some of the most astonishingly beautiful poetry I’ve ever read, dedicated to his big brother. It was an honor to get to hear about many of the special memories he shared with someone he loved so much.”

– Harley Tonelli

Pongo Poetry Project Writing Mentor

“A Wishing World” comes from a Pongo youth writer at the Echo Glen Children’s Center (their name, age and identifying details are not shared to protect their confidentiality). In the poem, reproduced below, this young person vividly recounts the heartbreaking scenes from the night of his brother’s passing, and the depths of the pain he continues to feel after his loss:

T, when I look into your eyes, I just see myself.

Brother, I got you stuck in my head inside this cell.

When I walk inside that house

I wish you could see me in here.

Talking to your mom, it hurts to hear her fear.

I remember the smell of that house and how we’d rock them baggy jeans!

Brother life feels so much harder without you next to me.

I remember that night at the park

When I remember that night it makes me wanna cry.

We used to always hoop but since I lost you

I’ve been feeling traumatized.

Brother, I remember I cried when your mama cried.

Listen, there is more to life than the eye can see.

There is so much more than the life people live.

Life is short, not just in the life we live.

So give it the most there is to give.

This piece, along with so many others, reminds us of the power in providing safe, judgment-free spaces for youth to articulate the suffering they too often carry silently. And while this youth writer movingly describes the debilitating impact of the loss of their brother, “A Wishing Well” closes on a more hopeful note that speaks to how self-expression supports young people in the wake of traumatic experiences.

The Science Behind Expressive Writing

In the aftermath of childhood trauma, particularly for those lacking the support they need to recover from it, young people often feel stuck, unable to see beyond their most tragic moments. Clinical psychiatrist and researcher Dr. Ted Rynearson describes how exposure to violent death among young people is often followed by “prolonged signs of complicated and traumatic grief,” including depression, post-traumatic stress, nightmares, and flashbacks that persist for years after the loss itself. Many young people feel as though the pain and sorrow they’ve experienced are definitional to who they are and their futures. Through the process of poetry writing, young people put their sorrow on the page, demonstrating to themselves that their traumatic experiences, while difficult, are just that; distinct events that they can process, draw meaning from, and most critically, move on from. Evaluation data from our programming shows that 74% of Pongo youth writers discussed a topic they had never shared before, and that 98% felt better after their Pongo experience. A study of the “Restorative Retelling” intervention, pioneered by Dr. Rynearson and designed to help survivors of violent deaths process their trauma and grief, demonstrated similarly promising results. Using a combination of Pongo-like writing activities along with other stress reduction techniques, the study found that depression and PTSD symptoms among violent death survivors “decreased significantly over the course of treatment.”

In the aftermath of childhood trauma, particularly for those lacking the support they need to recover from it, young people often feel stuck, unable to see beyond their most tragic moments. Clinical psychiatrist and researcher Dr. Ted Rynearson describes how exposure to violent death among young people is often followed by “prolonged signs of complicated and traumatic grief,” including depression, post-traumatic stress, nightmares, and flashbacks that persist for years after the loss itself. Many young people feel as though the pain and sorrow they’ve experienced are definitional to who they are and their futures. Through the process of poetry writing, young people put their sorrow on the page, demonstrating to themselves that their traumatic experiences, while difficult, are just that; distinct events that they can process, draw meaning from, and most critically, move on from. Evaluation data from our programming shows that 74% of Pongo youth writers discussed a topic they had never shared before, and that 98% felt better after their Pongo experience. A study of the “Restorative Retelling” intervention, pioneered by Dr. Rynearson and designed to help survivors of violent deaths process their trauma and grief, demonstrated similarly promising results. Using a combination of Pongo-like writing activities along with other stress reduction techniques, the study found that depression and PTSD symptoms among violent death survivors “decreased significantly over the course of treatment.”

Creative expression is also a powerful tool for remedying the reticence and shame that many young people feel about communicating the traumas they’ve endured. Harley, the talented mentor who helped facilitate “A Wishing Well,” noted that prior to authoring this moving piece, “this young person was clear” that “he did not consider himself a writer.” While this may seem jarring in the face of an affecting poem like “A Wishing Well” the sentiment is one we frequently encounter among the young people we serve.

Creative expression is also a powerful tool for remedying the reticence and shame that many young people feel about communicating the traumas they’ve endured. Harley, the talented mentor who helped facilitate “A Wishing Well,” noted that prior to authoring this moving piece, “this young person was clear” that “he did not consider himself a writer.” While this may seem jarring in the face of an affecting poem like “A Wishing Well” the sentiment is one we frequently encounter among the young people we serve.

Pongo’s work aligns with research-backed interventions such as Restorative Retelling, which has been shown to significantly reduce PTSD and depression symptoms in grieving youth. Our data reinforces this impact:

- 74% of Pongo youth writers discussed something they had never shared before.

- 98% reported feeling better after their poetry experience.

- 92% intended to continue writing after their first Pongo session.

The impact of this is twofold; not only do young people feel better equipped to talk about their pain but when experiencing hardship in the future, they can rely on the healthy coping mechanism of poetry writing in place of alternatives that may harm themselves or their futures.

“I felt relieved talking about things through writing that I didn’t usually talk about. Being in such a horrible place and then having all these joyful people come in to help us, it was kind of like an ambulance coming to a car wreck.”

– Pongo youth writer describing their program experience

This is why Pongo exists. To support young people in making sense of crises and to demonstrate that a community of people care about their suffering; to equip youth with a tool for voicing their turmoil, and imagining a future beyond it. As Joyal Mulheron, Evermore’s founder notes, “our grief is as unique as the relationships we hold” but “bereavement is systematic” and “the systems around us failed.” Evermore’s leadership in advocating for the comprehensive bereavement support we all deserve is vital to building healthier communities where flourishing in the aftermath of trauma is possible. We invite you to reflect on what it truly means to show up for young people–to address the root cause of their pain rather than respond to the symptoms of it–and what we gain as a society when we do.